Everybody knows the Thousand and One Nights. Not many people are aware of the long and varied story hidden inside its pages.

As many oral-transmitted texts, the Thousand and One Nights is a composite work. The frame story, along with the first and more ancient core of tales, came from India and Persia. This part was probably translated into Arab and handwritten for the first time around the 8thcentury. Arab stories were added in Iraq in the same period, among them some of the notorious tales about the Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Afterwards, independent sagas were added, followed by stories from Syria and Egypt. The Egyptian collection showed a preoccupation with sex, magic and low life that is almost absent in the two oldest cores. Eventually, the book was long enough to fulfil its promise of 1001 nights of tales.

The first European version was translated into French by Antoine Galland. As a source he used an Arabic text of the Syrian recension. An interesting fact about this version is that some of the most common tales, among them “Aladdin’s Lamp” “Simbad” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves”, do not exist in the original Mid-Asian version. As Galland wrote, he heard them from a Syrian Christian storyteller from Aleppo. This version reached an immediate and lasting success, being re-published and translated throughout all Europe until late 20th century. This version shows clearly the signs of its time. The text is adapted to the taste of the 17th century France and it has been heavily censored. It is good to remember that in that period and place, translation was often more an adaptation. Translators felt free to change or remove any part of the original they felt unnecessary or poorly written. Nevertheless, this is the version most known to the Occidental world and its legacy is undisputed.

In many other European translations, contents considered exaggeratedly explicit or violent were removed. Stories from the original manuscript were left off, and their place was taken by modern tales heavily influenced by Modern Romanticism, like those previously mentioned. The original stories are often permeated by racism. Different translators smothered or emphasized this trait according to their own beliefs.

In 1986, René R. Khawam published a new French translation of the most ancient core of tales. For more than 20 years he studied and confronted the oldest Arabic versions ever retrieved. His goal was to provide a trustworthy translation, which was both philologically accurate and possessed artistic value. He maintained the original register, which varied from the very low speak of peasants to the high and convoluted discussions between members of the nobility. All the poems that embellish the original text, and that were often removed or translated in prose, were carefully preserved.

In 2008 a new English edition, translated by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons, was published. This is a complete and modern translation of the Egyptian recension and contains all the “non-standard” stories. All the poetry is included, this time as plain prose paraphrase that does not attempt to reproduce the original internal rhyming. Moreover, this edition has cuts and it streamlines some of the most verbose parts. In this sense, it is not a complete translation.

When it is impossible to access the original text, it is up to the reader to decide what translation fits him most, according to his personal taste and preferences.

Author: Fulvio Spagnul

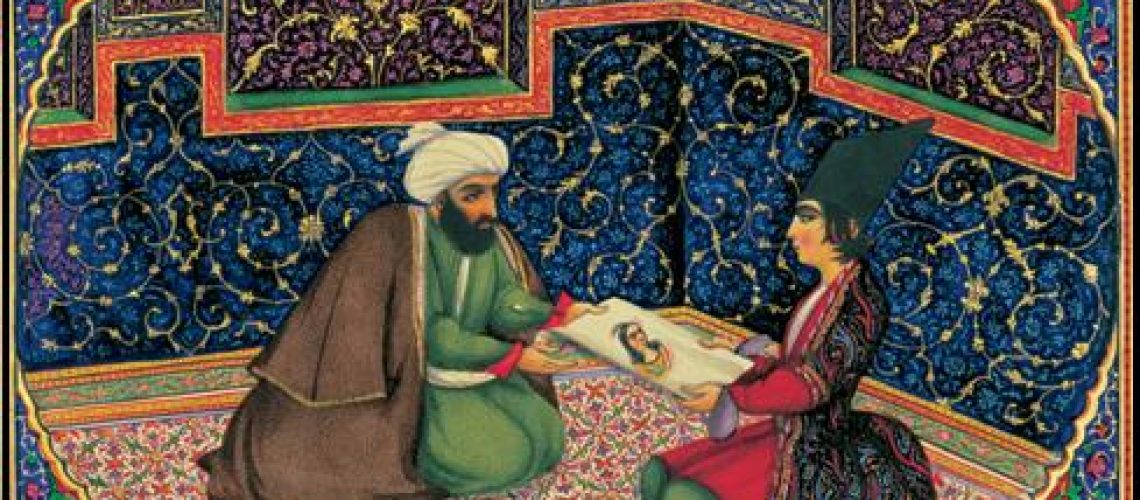

![Thousand and One Nights [cml_media_alt id='6877']The Tale of the Husband and the Parrot.[/cml_media_alt]](https://translit.misc.gainlinevpc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2-1001-nights-Arthur_Szyk_1894-1951._Arabian_Nights_Entertainments_The_Husband_and_the_Parrot_1948_New_Canaan_CT-220x300.jpg)

Link to image: The Tale of the Husband and the Parrot